Discover more about S&P Global’s offerings

Published: November 30, 2023

We reviewed more than 1,200 defaults of publicly-rated issuers since 2008 to better understand the impact that private credit can have on defaulters.

We observed a modestly higher share of selective defaults (and repeat defaults) among defaulters with private credit funding than among those without.

Notably, we found a somewhat shorter average time between defaults for those repeat defaulters with private credit funding than without.

However, we observed fewer repeat defaults and a longer average time between defaults from issuers that received private credit for restructuring purposes than from those that received private credit for other purposes or those without private credit.

Higher-for-longer interest rates present a challenge for borrowers that have grown accustomed to the historically low rates of the past several years. S&P Global Ratings reports that global corporate defaults have nearly doubled this year — with 127 defaults globally through October — even as default rates remain just above their long-term average levels. Distressed exchanges and repeat defaults are contributing to this total.

For borrowers struggling with cash flow or liquidity concerns, financing conditions remain particularly challenging, with broadly syndicated loan issuance at its lowest level through September since 2010, according to LCD Pitchbook, and ‘CCC’ category bond issuance at its lowest since 2008.

Amid the slowdown, many borrowers are turning to private credit for funding options.

To better understand how the growing involvement of private credit may affect future defaults, we reviewed 1,232 defaults that took place between Jan. 1, 2008, and March 31, 2023, from 979 issuers that were publicly rated by S&P Global Ratings in the US and Europe. These include many re-defaulters, or repeat defaulters with more than one default during this period. Using private debt deals data from PreqinPro, we then identified a subset of 97 of these defaults (from 81 issuers) where issuers had received private credit funding within a year and half before or after the default.

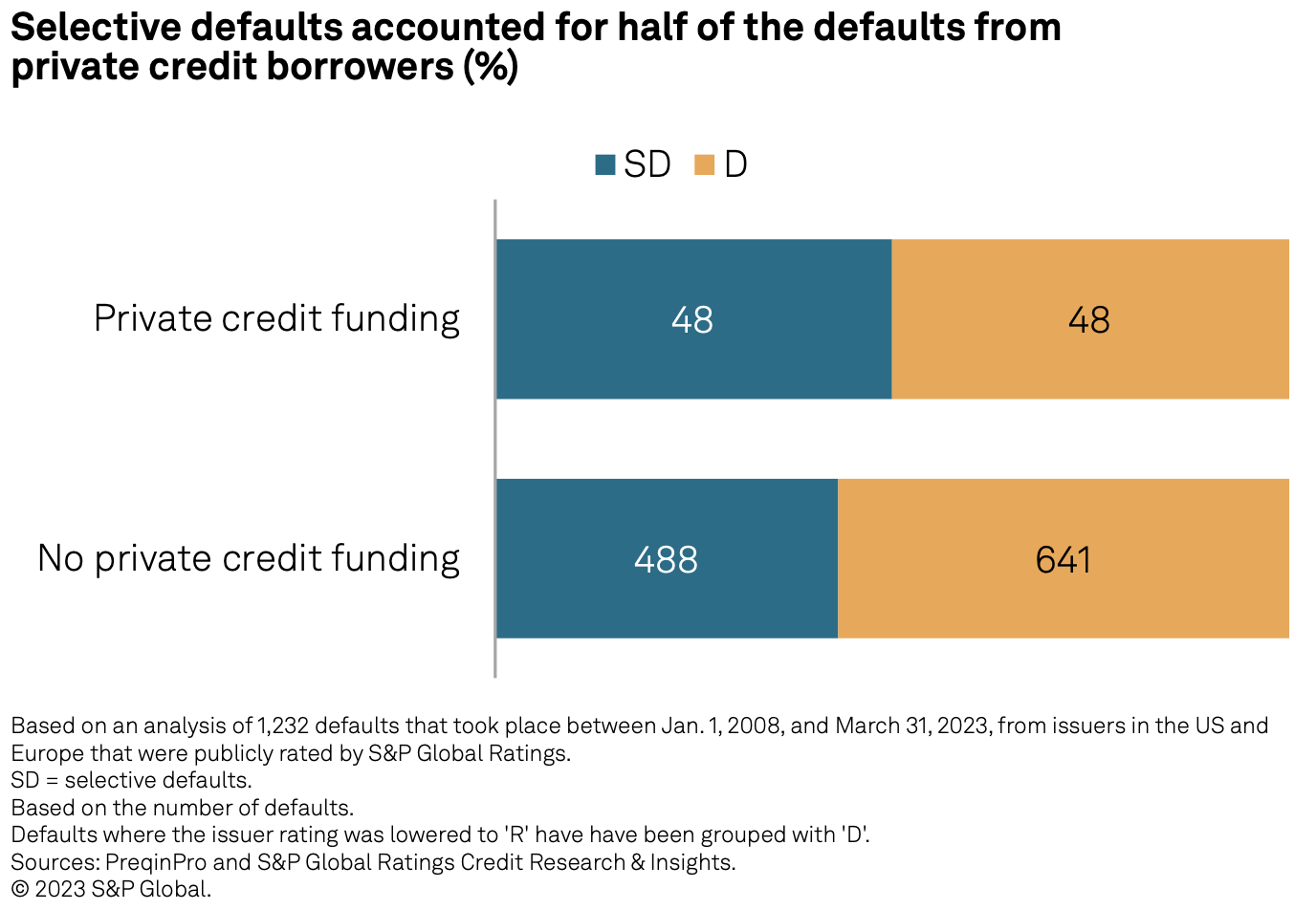

We observed a higher share of selective defaults among defaulters with private credit funding than among those without private credit funding. Half of the defaults from issuers with some private credit funding (50%) were selective defaults, compared with 43.2% of the defaults from issuers with no private credit funding.

Many factors may sway a borrower under duress to prefer an out-of-court restructuring over a traditional bankruptcy or a general payment default. Apart from keeping control of the entity, the issuer can also avoid potentially a long and costly bankruptcy and preserve more of its asset value. However, the success of a distressed exchange depends on the borrower’s ability to reach an agreement on terms with the lender to avoid a general default.

Private credit borrowers tend to work closely with a small number of direct lenders, which means fewer parties would be involved in a distressed exchange negotiation.

While private credit is another pillar of funding in the leveraged finance market, along with speculative-grade bonds and broadly syndicated leveraged loans, there are some characteristics that set it apart. Private credit borrowers have tended to be smaller (often with EBITDA of $25 million to $100 million, often with simpler debt structures, including unitranche) and the deals have fewer lenders. Frequently these are borrowers backed by private equity sponsors. Notably, with the growth of the private credit market and the rise of club deals (that involve a small group of lenders), larger borrowers with more involved transactions have tapped the private credit market.

Private credit borrowers tend to work closely with a small number of direct lenders, which means fewer parties would be involved in a distressed exchange negotiation.

While private credit is another pillar of funding in the leveraged finance market, along with speculative-grade bonds and broadly syndicated leveraged loans, there are some characteristics that set it apart. Private credit borrowers have tended to be smaller (often with EBITDA of $25 million to $100 million, often with simpler debt structures, including unitranche) and the deals have fewer lenders. Frequently these are borrowers backed by private equity sponsors. Notably, with the growth of the private credit market and the rise of club deals (that involve a small group of lenders), larger borrowers with more involved transactions have tapped the private credit market.

Chart 1

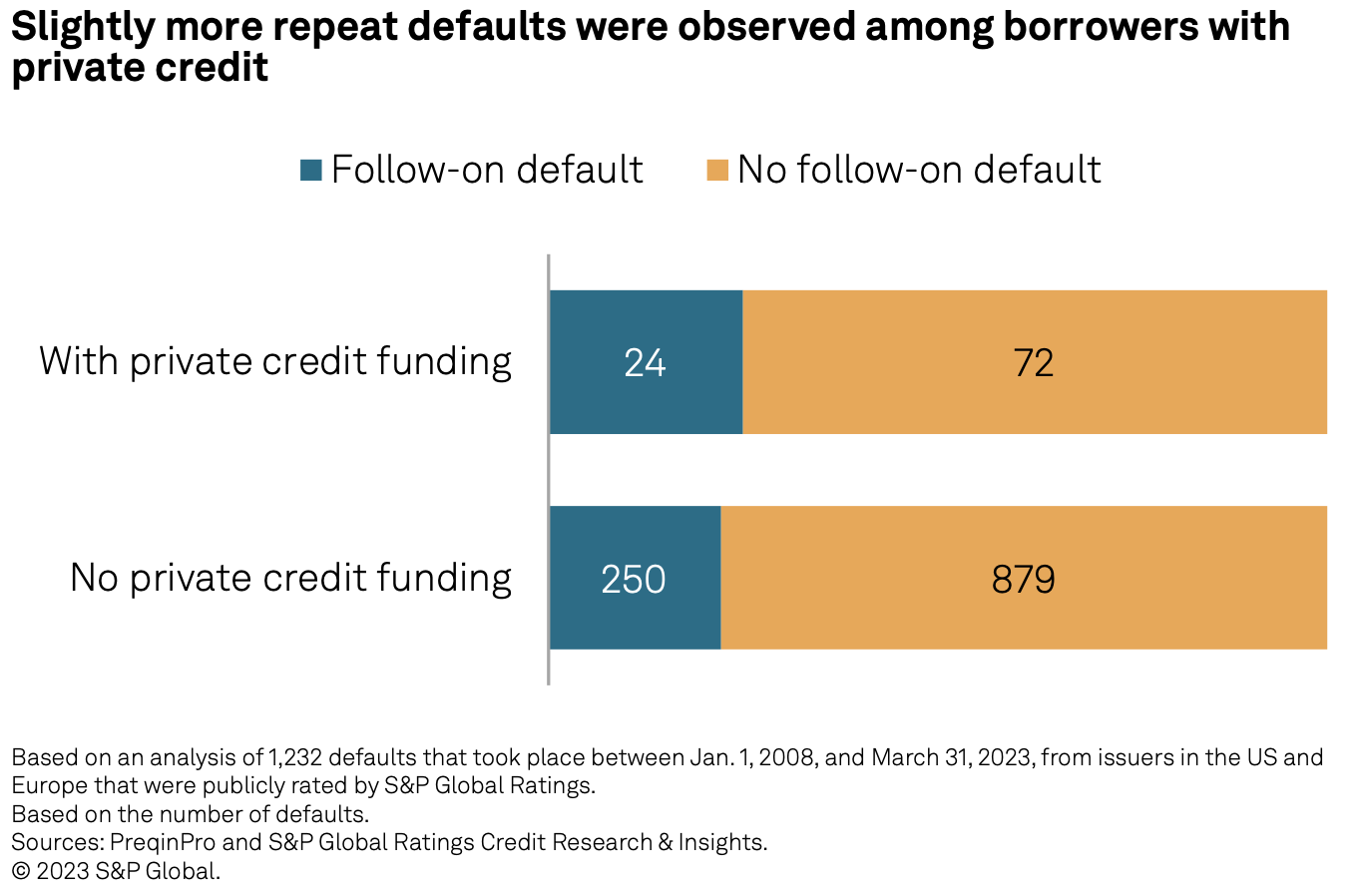

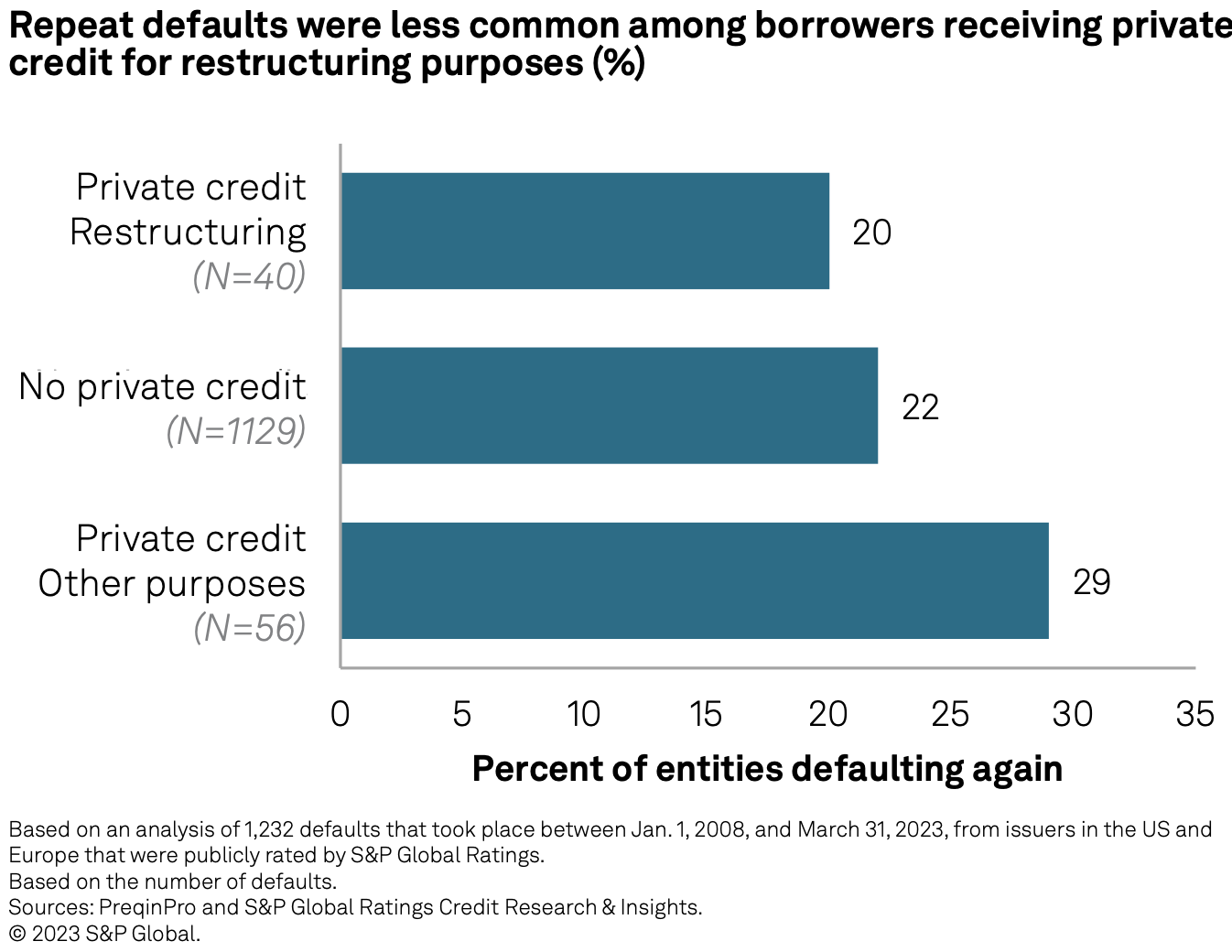

Repeat defaults were about as common among borrowers with private credit as those without. Normally, repeat defaults (or re-defaults) are more common following a selective default (such as a distressed exchange) than following a general default. However, we observed a less pronounced difference in the share of re-defaults among defaulters with and without private credit funding. Even though selective defaults were more common among those with private credit, we observed repeat defaults after 25% of the defaults of issuers with private credit, just three percentage points higher than among those without private credit.

With fewer lenders involved, and with typically fewer creditor classes involved, there’s more room for lender and borrower to be aligned toward reducing transactional costs and to execute efficient restructurings, which preserves enterprise value. In cases where a borrower is under stress, direct lenders can work closely with the private credit borrower on a debt workout, where a borrower with broadly syndicated loans may have to deal with several borrowers and classes and incentives of multiple creditor classes.

When the incentives of the direct lender and the borrower are aligned, the lender may make concessions such as waiving covenant defaults or allowing for payment-in-kind (PIK) in place of cash interest payments. This can buy time for a portfolio company to weather its storm and get to surer footing to meet its financial obligations.

Private credit is often used to fund private equity-sponsored companies. These deals can take many forms, including funding for growth opportunities, strategic acquisitions, and restructurings as well as leveraged buyouts and dividend recaps. While these deals can provide capital for growth and expansion, financial sponsors look to maximize their returns by adopting high levels of leverage for portfolio companies. S&P Global Ratings assumes a financial sponsor-owned company to be highly leveraged under our criteria.

If a borrower is loaded with an unsustainable level of debt, weakening its ability to navigate unforeseen challenges, it may be left treading water before an eventual default...or defaults.

We observed repeat defaults after 25% of the defaults of issuers with private credit, just three percentage points higher than among those without private credit.

Chart 2

Among the defaulters that we reviewed, we found several such examples.

One example of a borrower that ran into financial difficulties that led to multiple defaults after it took on too much debt was David’s Bridal.

David’s Bridal filed for bankruptcy in 2018 in a restructuring that erased roughly $400 million in debt from its books and turned ownership over to its lenders. Existing lenders also contributed new debt financing to support the turnaround. However, a subsequent default followed five years later.

David’s Bridal filed for Ch. 11 bankruptcy protection in April 2023, which resulted in a no-cash bankruptcy sale in July put the chain to business development company CION Investment Corporation. Cion’s acquisition included the assumption of certain bankruptcy related liabilities and an investment of $20 million into the business, and enabled the company to avert a total shutdown, with 195 stores (from about 300) remaining open.

Another such example, S&P Global Ratings lowered the issuer credit rating to ‘D’ in April 2019 of telecommunications company Fusion Connect, Inc. after it filed for Ch. 11 bankruptcy. A year earlier, Fusion had borrowed $680 million to fund reverse mergers with Birch Communications Holdings, Inc. and MegaPath Holding Corporation in 2018, but revenue growth post-merger fell well short of projections.

This restructuring wiped $400 million in debt from Fusion’s books and brought a $115 million exit financing loan. It also placed Fusion’s former lenders as its new owners. Despite this restructuring, Fusion continued to struggle. Fusion conducted a subsequent distressed exchange in January 2022, with a debt for equity swap that made Morgan Stanley Private Credit the company’s majority owner.

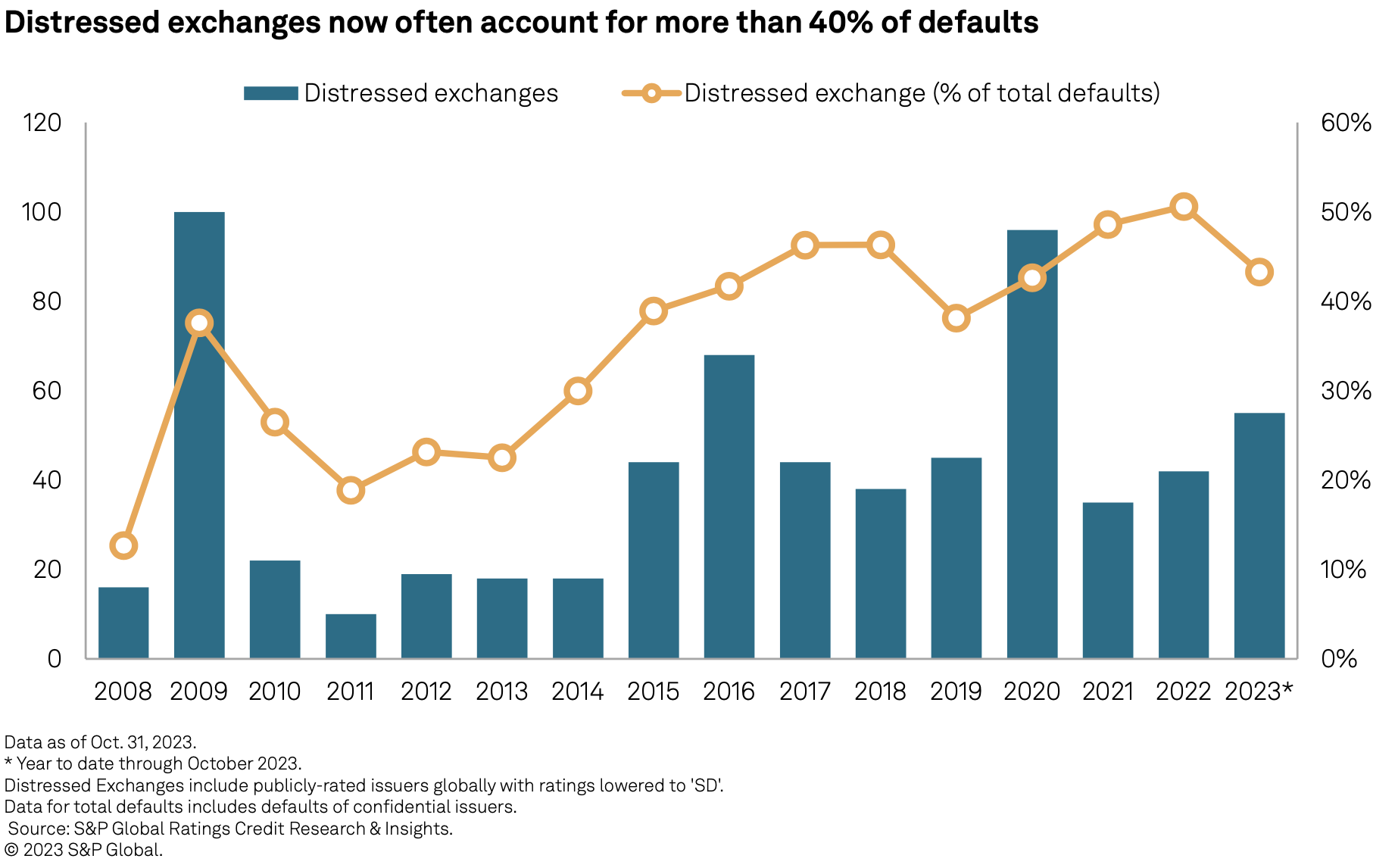

Fusion’s distressed exchange in 2022 is one example of a trend we’ve observed of the increase in distressed exchanges as a share of defaults. Since 2008, S&P Global Ratings has detected a marked increase in the percentage of distressed exchanges as a share of defaults. Half of defaults in 2022, and over 40% of defaults this year through October, have been distressed exchanges, and this is up from a range of 20%-30% in 2010-2014.

Chart 3

This matters because a rising share of distressed exchanges may indicate future default pressure. We’ve observed that re-defaulters (or issuers with multiple defaults) were nearly five times more likely after a selective default (such as after a distressed exchange) than after a general default within a 48-month period post-default. S&P Global Ratings found in A Rise In Selective Defaults Presents A Slippery Slope, June 26, 2023, that repeat defaults occurred after about 34.9% of distressed exchanges within a 48-month period.

The growing prevalence of distressed exchanges among defaults could lead to more defaults on the horizon in cases where the borrower’s debt position remains unsustainable following the exchange.

Among the re-defaulters, the time to default between the initial default and the subsequent default can vary substantially. At the long end, a handful of the re-defaulters lasted more than 10 years between defaults, while at the short end, a few borrowers had less than 20 days in between defaults.

In some cases where there is little time between defaults, an initial selective default can be a trigger that leaves the borrower with few alternatives besides a bankruptcy restructuring. One example of this is House of Fraser (UK & Ireland).

The company conducted a distressed exchange on July 30, 2018, that resulted in the withdrawal of an offer by C. Banner to acquire a majority stake in the firm in a deal that would have provided cash equity relief. House of Fraser is one of the defaulters for which we have no record that it received private credit funding, and once C. Banner’s deal was off the table, House of Fraser was left facing heightened liquidity and insolvency risk as it was confronted by a lack of funding options. House of Fraser subsequently entered its operating subsidiaries into administration 11 days later, on Aug. 10, 2018. Through this pre-packaged bankruptcy, it agreed to a sale of the company to Sports Direct (now Frasers Group).

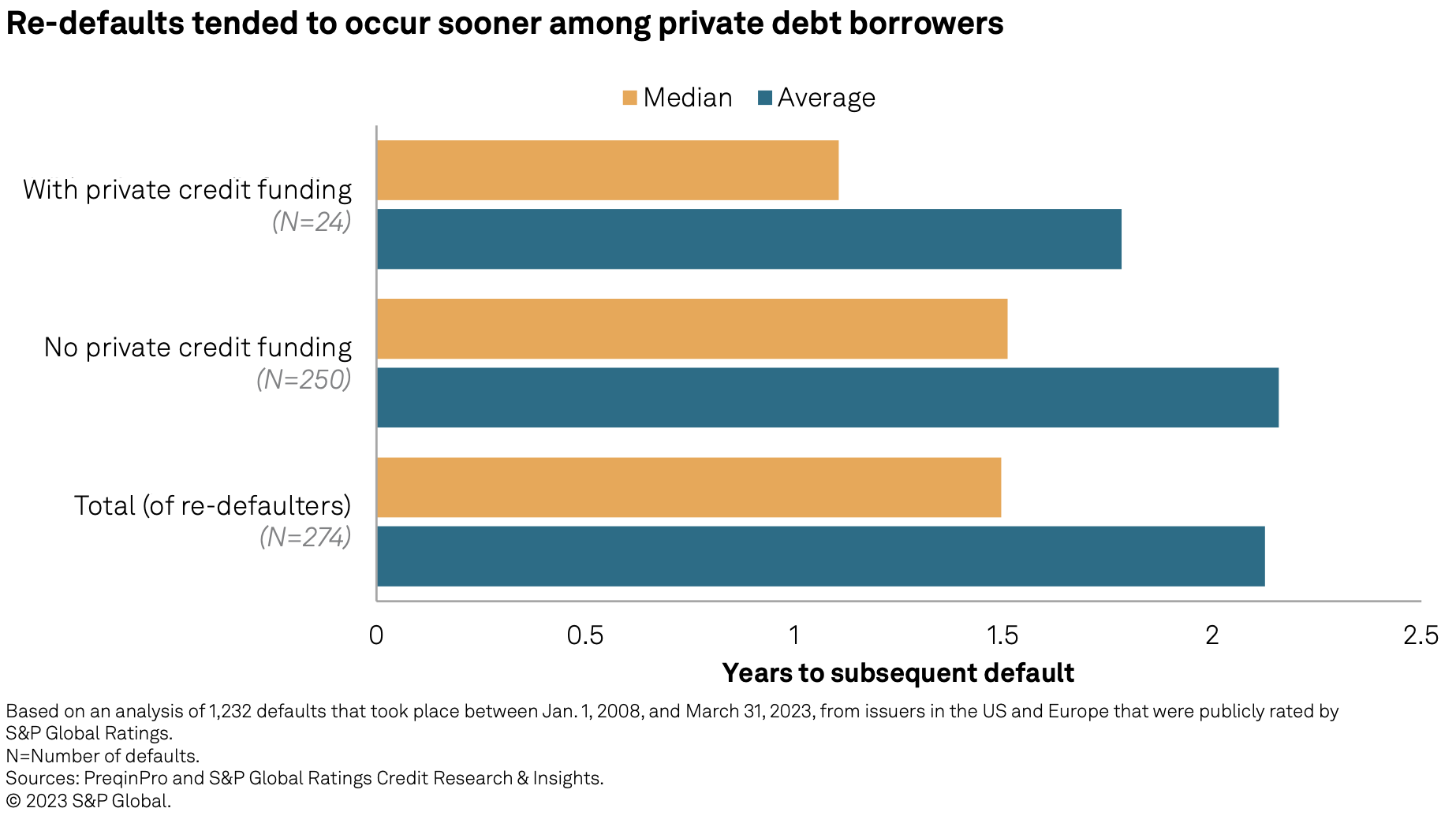

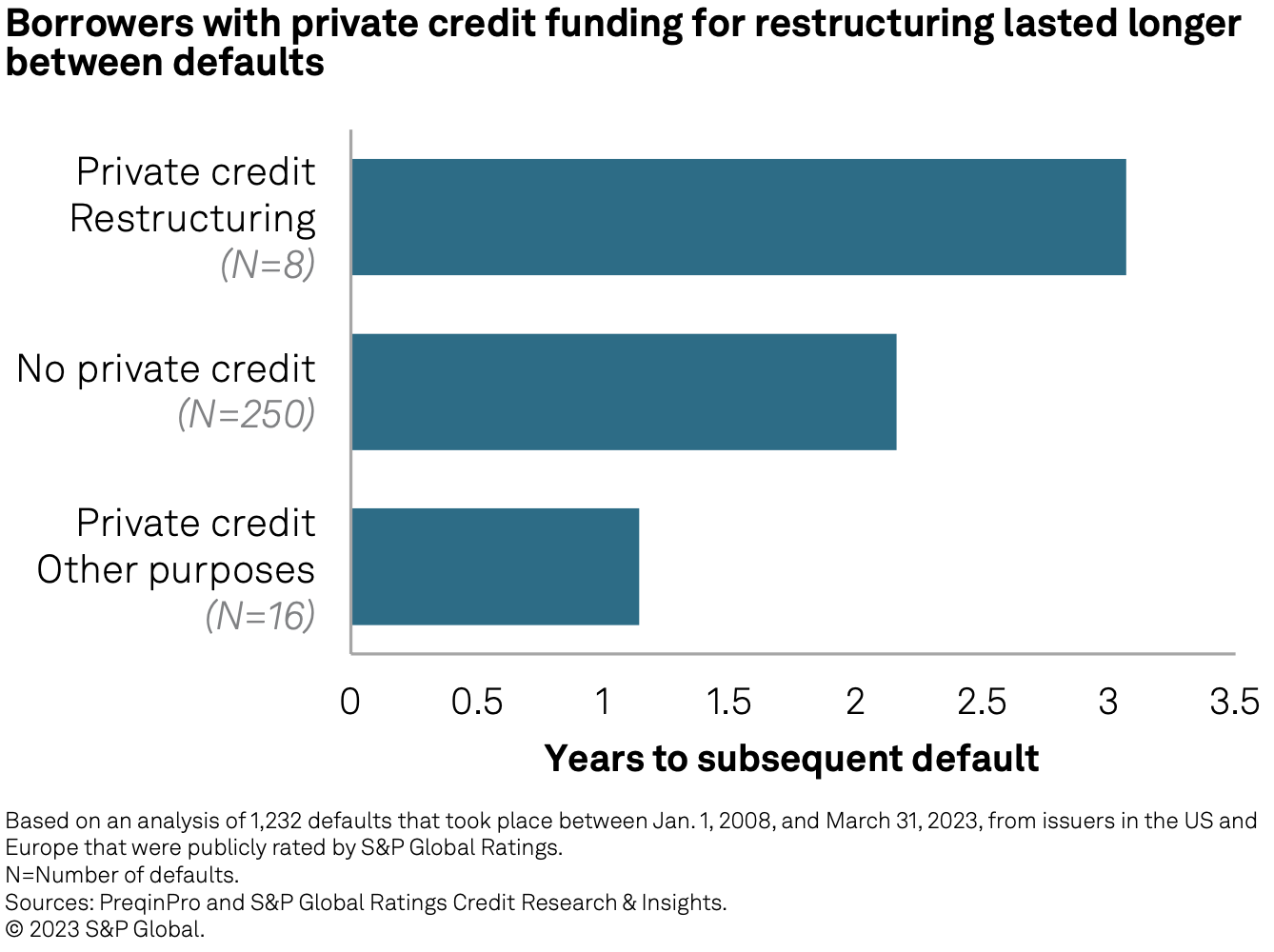

We found a somewhat shorter average time between defaults for re-defaulters with private credit funding than without. This shorter time between defaults could reflect firms with debt structures that are too aggressive or even unsustainable. Among the re-defaulters we observed, the average time between defaults was about 2.2 years for those without private credit, versus about 1.8 years for those with private credit. The median time between defaults was somewhat shorter, closer to 1.1 years for borrowers with private credit versus 1.5 years for those without.

There are a few characteristics of private credit that could contribute to this shorter time between defaults. First, there is the higher concentration of private equity sponsors and leveraged buyouts among private credit borrowers that can correspond with more aggressive financial profiles. Another potential factor is financial maintenance covenants, which are more common among private debt than among broadly syndicated loans. These covenants can serve as an early warning system for a lender that their credit is in trouble, potentially heightening the need to arrange a restructuring sooner rather than later.

Among the re-defaulters we observed, the average time between defaults was about 2.2 years for those without private credit, versus about 1.8 years for those with private credit.

Chart 4

However, even though the time between defaults for re-defaulters with private credit is shorter than for those with no private credit funding, we see variations emerge based on the deal type for the funding that was received.

Re-defaults were less common among those issuers that received private credit for restructuring purposes than among other entities, including those that received private credit for other purposes, as well as those without private credit.

In these cases, the work between borrower and lender to arrange restructuring funding may be able to help put a borrower on stronger footing to weather a difficult period. One example of such a turnaround, Gibson Brands, Inc., manufacturer of some of the world’s best-known electric guitars, turned to private debt after declaring Ch. 11 bankruptcy in May 2018. The restructuring deal allowed lenders to swap debt for equity, which allowed one of the firm’s largest debtholders, KKR & Co., to take control of the company. Gibson exited bankruptcy less than six months after its default in 2018 and has not subsequently defaulted.

Chart 5

Re-defaults were less common among those issuers that received private credit for restructuring purposes than among other entities

While a sponsor may make an injection or a direct lender may extend loans for restructuring to help a company get back on firm footing, the success of such contributions is not guaranteed.

One such example is from an issuer with multiple defaults as it struggled to adapt in a changing marketplace. Even the involvement of a trio of private market players in the 2010 Ch. 11 bankruptcy restructuring of supermarket operator The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company, Inc. was not enough to stave off future defaults.

After the restructured A&P emerged from bankruptcy as a private company in 2012, it declared Ch. 11 bankruptcy a second time in 2015 and closed for good in November 2016. Ultimately, the company cited the cost of its heavily unionized labor force as reason for the second bankruptcy, even as it had also been losing market share to competitors as it struggled to adapt in the highly competitive grocery space.

However, among the issuers with repeat defaults, those that received private credit for restructuring lasted longer between defaults than other borrowers. Those re-defaulters with private credit for restructuring averaged just over three years between defaults, compared with two years between defaults for those with no private credit, and nearer to one year for those receiving private credit for other purposes.

However, among the issuers with repeat defaults, those that received private credit for restructuring lasted longer between defaults than other borrowers.

Chart 6

The most pronounced example of this was luxury department store Barney’s New York, which defaulted through a distressed exchange in 2012 that turned control of the firm over to private equity firms Yucaipa Cos. and Perry Capital in a deal that reduced the firm’s debt by over 90%. Barney’s was able to survive for seven more years before it subsequently filed for Ch. 11 Bankruptcy in 2019 and liquidated in 2020.

In the best outcomes, a contribution of new capital for restructuring from the PE sponsor or additional loans from new or existing lenders, helps the borrower meet liquidity and capital needs and gives it some runway to weather the storm until business and economic conditions improve.

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, private credit lenders were willing to make concessions or contribute additional funding to their portfolio companies to allow time for business conditions to improve. As that period wound up being one of the shortest (and steepest) recessions on record, things returned to normalcy very soon.

However, the macroeconomic landscape is changing, with both borrowers and alternative investment managers potentially challenged by higher-for-longer interest rates, coupled with the specter of slowing growth. In such a scenario, private equity firms could find themselves in a position where they need to choose which of their existing portfolio companies to support. For the private credit lenders, they may have to grant more concessions; we are already seeing more instances of either push back of maturities and classes deferring interest.

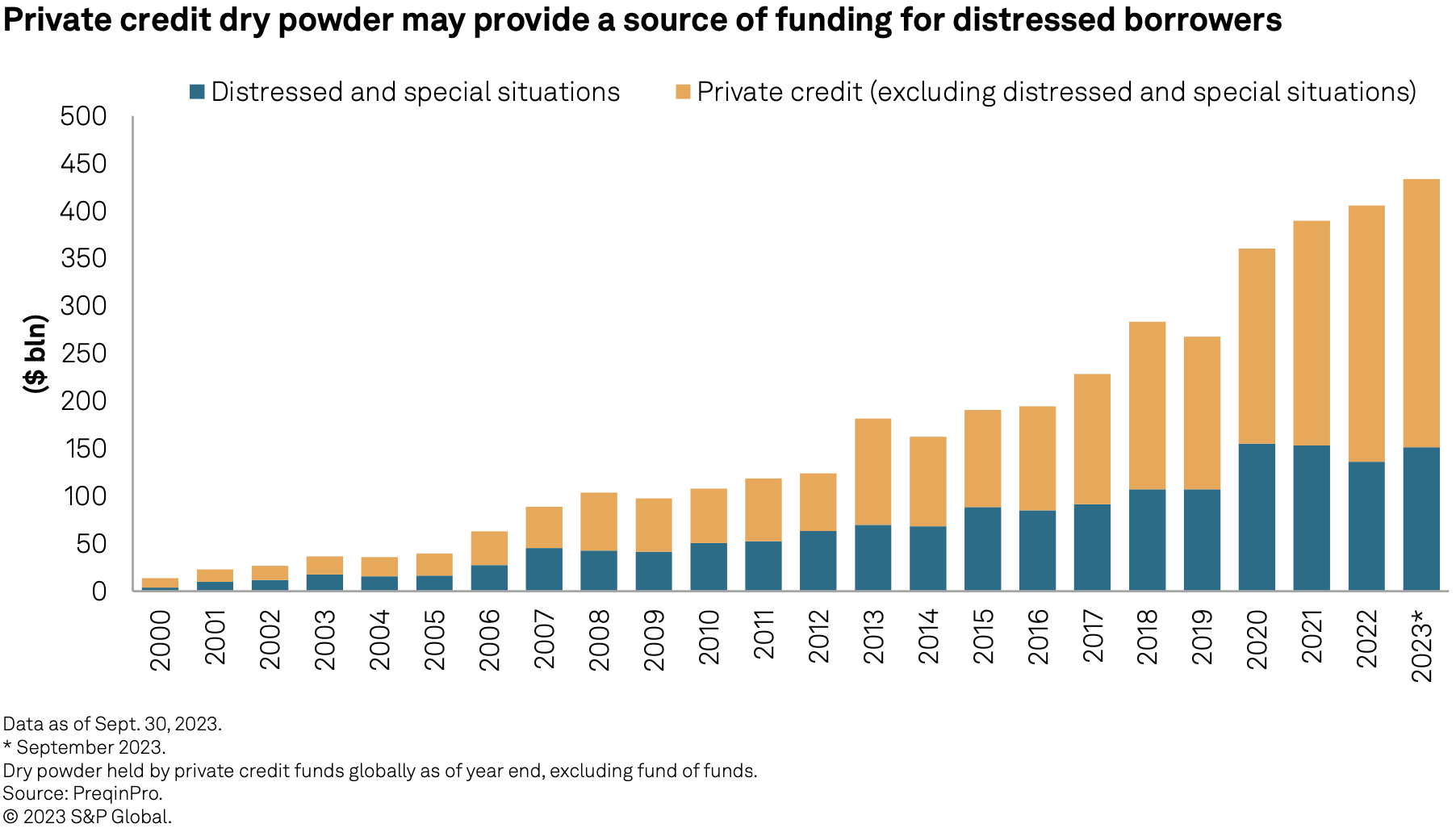

That said, plenty of private credit dry powder remains on the sidelines.

During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, private credit lenders were willing to make concessions or contribute additional funding to their portfolio companies to allow time for business conditions to improve.

Dry powder available for private credit lending has swelled as investors have increased allocations to private credit funds. While this dry powder serves as a source of funding for new deals and new investments, private credit funds may also hold some of this in reserve for reinvestment in struggling portfolio companies. Private credit firms currently have more than $400 billion in dry powder according to PreqinPro. Of this, $150 billion is earmarked for distressed investments and special situations, providing lenders with a war chest to hunt for opportunities or support challenged portfolio companies should credit conditions weaken.

Private credit firms currently have more than $400 billion in dry powder according to PreqinPro. Of this, $150 billion is earmarked for distressed investments and special situations.

Chart 7

This pool of dry powder could be a critical source of funding for borrowers that are struggling to navigate headwinds of higher interest rates and challenging financing conditions. For companies on the precipice of default, liquidity is critical. The availability of funding, such as through private credit, can be the difference between a default or an eventual turnaround.

A note on the data used, in this study we exclude confidentially-rated defaulters. Furthermore, for issuers with private credit funding, we’ve attempted to capture repeat defaults, even if we did not assign a new rating in between the occurrences of default. An issuer that defaults, and then receives private credit funding, may be less likely to maintain a public rating than a borrower with debt consisting of bonds or broadly syndicated loans. In S&P Global Ratings’ ratings performance research, including in our default and transition studies, we treat a default as a terminal rating. A rating assigned following a default is treated as a new initial rating for the entity. However, private credit borrowers may be less likely to have a public rating, and so we’ve considered instances of repeat defaults (where there was no intervening rating) from these entities so as not to bias the data.

– A Rise In Selective Defaults Presents A Slippery Slope, June 26, 2023

– Private Lending: Time to Adjust the Sails, April 18, 2023

Diego Castells,

Editorial, Design & Publishing

Mahnoor Haider

Editorial, Design & Publishing

Diego Castells,

Editorial, Design & Publishing

Mahnoor Haider

Editorial, Design & Publishing